Wednesday 30 December 2015

Second article accepted!!

The editors of Ecology and Society have accepted the manuscript, composed by Jan van Tatenhove and me, entitled "Hydraulic engineering in the social-ecological delta: understanding the interplay between social, ecological and technological systems in the Dutch delta by means of 'delta trajectories'" for publication! I expect that it will be published next month.

Wednesday 23 September 2015

Light at the end of the tunnel?

While I'm struggling turning my thoughts into a written Phd I gave a lecture to first year master students last week about the approaches used in my PhD. Lovely enthusiastic and critical audience, great fun!

Prezi here

Prezi here

Friday 4 September 2015

Stockholm & water

For the last two weeks I’ve been in Stockholm, attending the Stockholm World Water Week (SWWW), followed by a research visit hosted by the Stockholm Environmental Institute (SEI). Both ‘events’ were a great opportunity to talk with many people about the topics I work and discuss about the particularities of the deltas where the research takes place.

At the SWWW, still, it is not easy to get immediately in touch with people working on or interested in similar topics – the seize of the conference (over 3000 people participated) and the broadness of the theme (water and development) made it very likely that you would connect with people working on totally different dimensions of water. It required some targeted, on-site researching and contacting.

So, I was happy that the week after the event was dedicated to planned and more focused discussions with ‘matching’ organizations and individuals when it comes to research topics. Besides SEI you can think about organizations such as the Global Water Partnership, the Stockholm Resilience Centre, and the Stockholm International Water Institute.

Today I gave a presentation at SEI about controlled flooding in deltas and discussed with the participants about how to conceptualize deltas, and how controlled flooding (and associated sedimentation processes) might contribute to building long term delta resilience – not only for humans inhabiting the delta, but also for the delta as a dynamic ecosystem itself. You can find the slides of the presentation via Slideshare. The conclusion was that the paper, written by Jan and me, which includes all these kinds of issues, will find a large community interested to read it and to continue thinking about dealing with delta flood dynamics ;p!

Monday 31 August 2015

The Delta Works of the 19th century

After fifteen years I re-visited a pumping station

near some of the deepest regions (located several meters below mean sea level)

of the Netherlands, which houses one of the world’s oldest museums dedicated to

hydraulic engineering: the Cruquius. The pumping station contributed to

draining the former Haarlemmermeer (‘meer’ meaning ‘lake’) between 1849 and

1852. After serving as a backup station it was formally taken out of service in

1932 and turned into a museum two years later. It now displays several

hydraulic pumps used in other projects, but most attention goes to the eight enormous

lift pumps and the central cylinder engine, which can still move - on

electricity, and no longer pump water.

The museum, which is housed in the pumping station’s

workshops, sends out message rests on emphasizing a continuous battle between

the Dutch and their ‘water wolf’. For example, it depicts a heroic Dutch lion

in the shape of the landscape of west Holland after the reclaiming the lake. The

names of the three pumping stations are after three hydraulic engineers who

brought forward plans for reclaiming the Haarlemmermeer: Jan Adriaanszoon

Leeghwater (plans dating back to the mid-17th century), Nicolaas

Kruik (Latinised name Cruquius, early 18th century), Frans van

Lynden van Hemmen (early 19th century) which also indicates a form

of ‘heroism’.

Before the pumping stations were constructed, water

management in polders and reclamation of small wetlands was mostly done by

using wind mills, (Archimedes’) screw pumps and water wheels, but in the late

18th century, steam driven engines step by step became employed in

hydraulic engineering works. The construction of three large pumping stations to

drain the Haarlemmermeer represented a solid establishment of using steam power

for land reclamation.

The Haarlemmermeer measured around 17,000 hectares,

which more than out-doubled the largest drainage project done so far by means

of wind mills (Beemster polder of around 7,000 hectares). Over the centuries

the lake had expanded gradually (eroding its shores, breaking connections to

nearby other lakes, as well as deepening up to 4 meters due to underwater peat

extraction). Although plans for draining the lake existed earlier, it necessitated

socio-political reasons, as well as the advent of hard wind and steam power

engines, to materialize. According to the museum, William the First (the first

king of the Netherlands) needed to improve his public image after Belgium

declared its independence from Holland in 1830. Also major storms in the 1830s,

extending the lake further, threatening the urbanizing cities along its edges. Reclaiming

the Haarlemmermeer could from this perspective be seen as a nation (re-)building

effort, attempted with steam engines in pumping stations displaying grandeur and

technological achievement.

Because besides its hydraulic background, a striking

feature of the pumping station is its architecture. When looking at the

station’s pictures, but even more when visiting its interior, it is hard not to

associate the structure to designs of churches or castles. Its buttresses,

lancet-shaped windows, battlements and keep support an authoritative

affirmation by the church and state power with the practice of ‘pumping out

water’. Therefore, well worth to pay it a visit and to learn more about this

feature of water management in the Dutch delta.

Photo Gallery by QuickGallery.com

Photo Gallery by QuickGallery.com

Wednesday 8 July 2015

Summer holiday reading material

Earlier this years I was finally introduced to the work of Amitav Ghosh through reading his great book "the Hungry Tide" about live in the chars of the Bay of Bengal.

During my summer holidays I read the wonderful book "The Glass Palace" by Amitav Ghosh. The book is an absolute page turner about the lives of three generations during the colonial times in Burma, India and Malaya. Best historic novel I've read since David Mitchells "The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet".

Before my holidays I read Flanagan's Man Booker prize winning "Narrow Road to the Deep North" about the experiences of Australian soldiers on construction sites of the infamous death railway. Both books opened my eyes to histories that I know very little of. Looking back on these two historical novels i was struck by the stylistic differences between the two, especially the ways and tone in which they describe the violent histories, but i could quite grasp what this difference was. Reading Ghosh's blog this morning I found this piece on Ghosh' blog that provides part of the answer.

Next up: the Ibis Trilogy!

During my summer holidays I read the wonderful book "The Glass Palace" by Amitav Ghosh. The book is an absolute page turner about the lives of three generations during the colonial times in Burma, India and Malaya. Best historic novel I've read since David Mitchells "The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet".

Before my holidays I read Flanagan's Man Booker prize winning "Narrow Road to the Deep North" about the experiences of Australian soldiers on construction sites of the infamous death railway. Both books opened my eyes to histories that I know very little of. Looking back on these two historical novels i was struck by the stylistic differences between the two, especially the ways and tone in which they describe the violent histories, but i could quite grasp what this difference was. Reading Ghosh's blog this morning I found this piece on Ghosh' blog that provides part of the answer.

Next up: the Ibis Trilogy!

Wednesday 6 May 2015

Second paper submitted: deltas as co-evolving social, ecological and technological systems

Last week I submitted my second paper to Ecology and Society. For those interested, here you’ll find a short version of the paper (or, extended version of the abstract ;p).

In its academic publications, Ecology and Society emphasizes the interplay between society and ecological systems. Since 2003 the journal has focussed on topics related to the management of ecosystems, of societal processes in relation to ecological processes, and on different modes of governance or politics involved with nature. Concepts such as resilience and adaptability originate in this field, trying to express states or capacities of complex and coupled socio-ecological systems.

What I found most interesting about the journal, and which is also highlighted in my paper, is the interplay between ecology and society. In my view this materializes in the form of technology or engineering, as a ‘mediating’ object. Remarkably, studies that explicitly use socio-ecological perspectives central to E&S writing (for example, some found that did so at the level of deltas: see Garschagen on the Mekong, and Pel et al on the Netherlands) often do not go into much detail about hydraulic engineering.

If we take the Netherlands as an example, we see that various types of technology have materialized, based on dynamics or processes or events in the natural system. These are constructed, some by means of ‘simple’ science and construction works, others by means of more complex models or high-tech engineering, following from social actors’ deliberation about overall policy and individual projects. Riverembankments or smaller dams can be examples of the former, while the Oosterscheldestorm surge barrier can be an example of the latter. Once constructed these objects start to have impact on both the societal (socio-economic developments behind the dykes, feeling of being safe) and natural (changed water and sediment flows) systems.

Interestingly, this leads to responses that reinforce the existence of the structure: embankments are raised over and over again, and the negative side effects of the Oosterschelde storm surge barrier are addressed as second-order problems. This sets the delta on a certain trajectory in which technology can arguably be said to already ‘sketch’ the direction, or future, towards which the delta is evolving as a whole. Researchers have argued that these trajectories are not very sustainable, and too rigid in nature, when seen over longer timescales.

There are options to move away from existing hydraulic engineering approaches. This come often at a huge price, and also with social resistance. An example is the Room for the River programme, which is to some extent based on river widening, but where many court cases were issued by affected local communities – which is very understandable. Other areas are the domain of eco-technology, eco-engineering or ecosystem-based flood management. These need closer research, but are said to bring societal demands, natural processes and technological possibilities more in tune with each other.

In conclusion, if we talk about delta ecosystems, and societies’ ‘dealings’ with them, this interplay often materializes in physical hydraulic engineering works: embankments, barriers, dams, sluices etc. Once constructed, they yield a long-term influence on the direction in which a delta trajectory is evolving. Although difficult to move away from, unsustainable delta trajectories could be reoriented by adopting ecosystem-based forms of engineering.

Hopefully the paper will be accepted by the editors of the journal for the review process, and once that has been completed successfully, it will appear online in a few months’ time!

Tuesday 17 March 2015

Hydraulic jungle

The Dutch version of Angkor Wat is located in the

Noordoostpolder. Overgrown, abandoned relics from a hydraulic ‘religion’ are

spread out in a deep ‘jungle’ called the ‘Waterloopbos’. It is not the first

time that this place has been mentioned (see this post about a visit of some of

my project colleagues some years back), but being an amazing sight worthwhile

to receive yet another blog and update. Even more important, the area is

targeted to receive its very own Master Plan (also check out the video)!

The forest itself dates back to 1944, and was planted in

one of the reclaimed Flevopolders. By the early 1950s the area was handed over

to the WL Hydraulics. This organization had an office in the Flevopolders and

was in need of an area to be used as a testing facility, or open air

laboratory, in which scale models of various hydraulic works could be tested on

various hydraulic characteristic. Interestingly, various decisions regarding

the place of a dyke, or layout of a harbour, have not been taken on site, but

in, or based on measurements, sometimes on the other side of the world, in a

small forest, in a typical Dutch ‘polder’.

For example, in small scale version (1:50), miniature

versions of the harbors of Rotterdam, Lagos and Bangkok appeared between the

trees, equipped with different types of docking quays and wave barriers, to

test with design and layout would suit the requirements of planned projects. Many

of the works implemented within the Delta Plan were constructed and tested

here, for example and the effect of waves and erosion during the closing of dams. After testing, however, those small scale models were just abandoned,

and became in turn the target of the forest ‘re-reclaiming’ the area with

overgrowing vegetation.

In the mid-90s WL Hydraulics moved to Delft. Plans of

the new land owner to convert the area into a recreational area with holiday

houses faced protests by nearby inhabitants and NGO’s advocating nature

protection and restoration. The NGO Natuurmonumenten was able to buy the area

in 2002, and developed various initiatives to keep the area accessible and to

capitalize on the various hydraulic scale models integrated in the forests’ walking

routes. The area is up for nomination and this will undoubtedly speed up the

formulation of a ‘Master Plan’ describing the future plans for the area.

Friday 30 January 2015

Historic water research in the Netherlands

Yesterday I participated in an event organized by the Vereniging voor Waterstaatsgeschiedenis (association of historic water research). Their yearly ‘research symposium’ highlighted and gave a very efficient overview of the type of research, and themes, that is currently taking place in the field of historic water research in the Netherlands. Very useful in relation to science and technology studies in which a historical perspective is often emphasized.

The

relation between disasters/water management and religion captured several

research projects that are being carried out in different historic time frames:

from religious explanations of disasters (later partly replaced by scientific

explanations) to religious motives to support disaster victims with money or

goods.

Another

group of projects deals with issues that can now be expressed by the term ‘governance’:

the involvement of various actors, including a formalizing state and moves to

adopt a more centralistic approach to dealing water. It became clear that

investing in projects, for example in impoldering (large) lakes in Holland was a

very risky business; and that when private investors (including the Church!)

did not take action, the state came into the picture to fund or coordinate

hydraulic works. Especially when ‘safety issues’ were felt important enough.

A specific

issue that was heavily debated were river ice floes. In the 17-19th

centuries this was a common problem in the river, which frequently caused dike

overtopping. It was argued that the various de-poldering projects (spreading

out the water over larger areas) was dangerous because shallow water freezes

quicker. Of course counter arguments were voiced: those de-poldered areas will only receive

water at certain water levels, during which water flows are very high. In

addition, I learned that Rijkswaterstaat

even has developed a protocol to deal with ice in the rivers. What was that thing with climate change again...

Ice encroaching near Ochten (source: http://www.weyerman.nl/9964/kruiend-ijs-1789)

But at the same time… these guys still talk about ‘dia’s’ instead of slides J.

Monday 26 January 2015

New case: controlled flooding in the Ems delta?

Many years

after its first publication in 1999, I closely re-read ‘De Graanrepubliek’ (in English:

The Wheat Republic). The author, Frank Westerman, is a graduate from a study

programme what is now called International Land and Water Management in Wageningen,

already many years back. Every bachelor and master student of this programme will

immediately recall the very strongly ‘suggestion’ of reading the book ;p.

Everybody probably

knows about the southwest delta – the delta where in 1953 a big flood hit the

Netherlands, and the region where the Delta Works have been constructed. But we

have another delta, the Ems delta, in the northeast

of the country, covering the province of Groningen. To be more precise, the

region can be classified as a Dutch-German delta, because a large part of the

estuary lies in Germany, and the river Ems that flows into the estuary comes

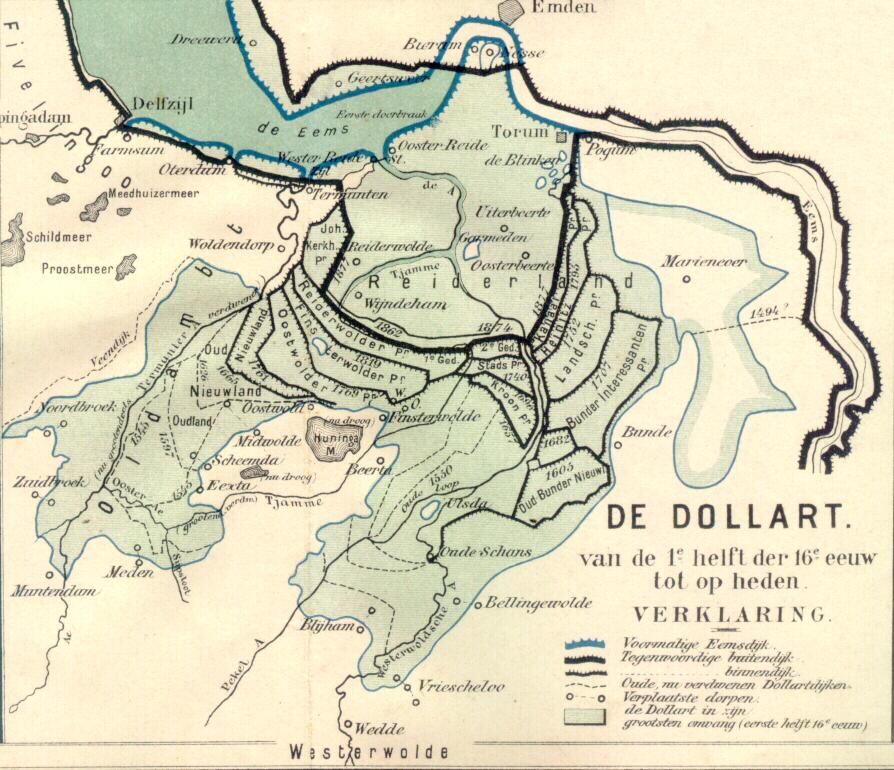

from there as well. The Dollard is a kind of spatial depression or delta lake in

open connection to the Ems, which is characterized by a century long history of

settlements, land reclamation, coastal flood disasters and flooding. Over time,

lands have been reclaimed and lost again (including settlements) to the sea several times.

(source: http://www.weikopiebes.nl/ and http://en.wikipedia.org/)

De

Graanrepubliek deals with developments in agricultural polders bordering the

Dollard. Those polders are typical ‘delta polders’ in the sense that the soils

are extremely fertile, supporting the most productive farms of the Netherlands

at the time. The farmers produced wheat – of similar importance as rice in food

production and consumption in the Asian deltas. The period after the 1960s was

socio-economically very dynamic: it was a time when discussions arose about the

relation between farmer workers, and the large farmer landowners that got rich by

producing wheat, the socio-political tensions that this brought, the interest

in socialism, mechanisation in agriculture, and the unification of Europe.

All these

developments contributed to what I study in my research: the flooding, or

de-poldering, of delta polders. The book describes how European agricultural

policy in the 1960s and 70s led to a huge overproduction of wheat. Realizing

that maintaining what in fact was a highly subsidized agricultural production system,

the Dutch Sicco Mansholt (who was actually born in Groningen, the Ems delta),

vice minister of for agriculture in Europe, reduced the formerly ‘guaranteed’

price that would be paid to farmers for their wheat.

The farmers

in the Ems delta felt the consequences. Farming wheat became much less

profitable, and new plans that were in favour of continued support for agriculture

did not pass through the political system. Instead, environmentalists and spatial

planners got enthusiastic about other uses of the delta landscape. Instead of

farming, which was said to be unprofitable, bad for the environment because of

its use of fertilizers and massive wheat production, those social groups wanted

the plan ‘Blauwe Stad’ (Blue City).

(Source: https://klaasantonmulder.wordpress.com)

Plan Blauwe

Stad wanted to flood some agricultural

polders in the delta and construct villages around a newly formed delta lake.

It was envisaged that many, especially rich city dwellers would favour a house

in such an area, with new nature and options for recreation, all supported by a

large water body covering some of the most fertile delta soils in the

Netherlands. This would stimulate a different type of economic activity in the region:

no more agriculture, but delta leisure. A long story short – the plan was

accepted and in 2005 about 1200ha

agricultural land was converted into 400ha of new nature and 800ha of water

(lake Oldambt).

Now,

several years later, Frank Westerman explains in an added chapter that those

expectations did not materialize. Only a very small percentage of the plots has

been sold, and the province has let go the original plan. It is now presented

as a nature development plan with some supportive economic activities and the

task to act as a water storage basin in times of high rainfall or river

discharge.

All in all

a very fascinating story. A typical delta story: dynamics at the border of land

and water, times of land (reclamation), of disasters (1877), and since recently

also of intentional flooding. But first, it’s time to prepare for a next delta

tour up north, to take a first-hand look!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)